The Charleston Peninsula

Written by Harlan Greene

When the summer of 1975 set in, I was adrift, having no idea what autumn, or the future, would bring. Like me, many of my friends had just finished college. Some had moved to New York and started graduate school or careers; most of us, though, were waiting for whatever the next step would be. We gathered each evening in downtown apartments that were large and dim with slanted floors and doors askew, Indian print spreads on couches, and Rorschach-like stains on the ceilings. No one had air conditioning, so we sat on porches, fanned ourselves, flicked ashes from our cigarettes into plants, and launched barely extinguished butts upward to the sky; as they fell, they looked like urban fireflies.

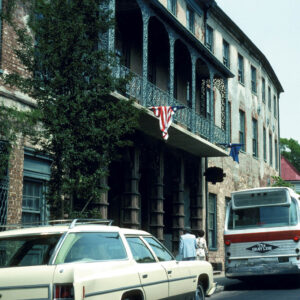

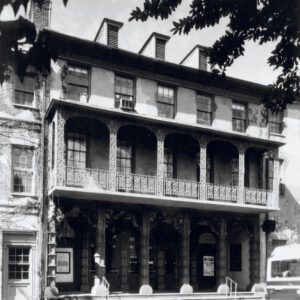

I was living atop the Dock Street Theatre without a car, but my bicycle was always at the ready. The grocery store known as the “Little Pig” on Broad Street (the big Piggly Wiggly was on Meeting and Spring) kept me supplied with white bread, peanut butter, and bologna. Silver’s and Woolworth’s had every gadget or amenity or shoelace anyone could need. There was a coin laundromat on Tradd as well as many corner stores, where men who stood drinking beers out of paper bags would sell two cigarettes for a nickel out of open packs.

We weren’t well-heeled enough for The Scarlett O’Hara restaurant at the foot of Charlotte Street and would never admit to entering the Embassy Supper Club near the Market (which was often deserted, haunted by winos, and smelled of urine). At Henry’s, we mustered our courage to talk to William Faulkner’s stepson, Malcolm Franklin, always in his safari suit at his habitual place at the bar. We drank in college bars and ended up at The Coffee Cup at Meeting and Wentworth at three in the morning, sitting between tugboat captains and drag queens, all of us obeying the sign that read, “Be Nice, Be Quiet, or Be Gone.” That seemed a good enough philosophy to follow as we waited for what our lives would bring.

I spent much of my free time walking through shabby neighborhoods with unpainted houses, like unwashed faces. I felt pulled along—around corners, down alleys—as if pursuing someone: me, or who I might become.

All summer long, I kept running into friends who claimed they had seen me and said, “Hello,” but rudely, I had not answered. I insisted I had been nowhere near that spot, but people swore I was lying, and so I began to wonder excitedly if I was a sleepwalker, or if someone was impersonating me, or maybe I had dissociated in the heat and had a split personality.

With trepidation and a sort of fondness, we kept tabs on the folks we saw on King Street, such as the “pencil man” who wore leg braces and a coat and tie as he begged in front of Woolworth’s; if you dropped a coin in his cup, you could take a pencil if you wanted (few did). Then there was the grizzled, soulful-eyed owner of the New Shoe Factory, who always stared dejectedly at passersby. Would we end up like them—living Charleston statues?

Wondering if we would ever break free of the gravitational pull of our native city, we longed for the change we feared as the newspaper prophesized new things. Maybe someone would build that bridge to James Island; and maybe folks would drive all the way to those islands, Seabrook and Kiawah, they were talking about developing. Our days seemed to repeat on a loop like the film that played endlessly at the Riviera Theater (I think it was Mandingo). Ashley Avenue would always go north; Rutledge, due south; Beaufain and Wentworth would be one-way eternally.

One day, a woman stopped me and said, “You look just like my son,” pointing to a nerdy guy coming our way. I didn’t think we looked at all alike, but we spoke a bit; he lived with his mother near the public housing projects on Queen Street. It was not my future, nor even myself I met that summer, just my doppelganger. By August, I decided to leave.

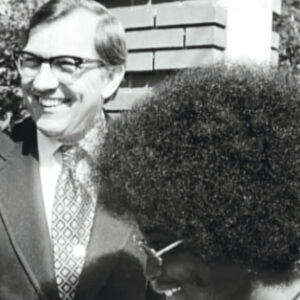

When I came back from California a year later, Charleston seemed changed. A thirtysomething year old fellow with horn-rimmed glasses named Joseph P. Riley Jr. was the city’s making-things-happen mayor, and something called Spoleto was being talked about. I got a job in a bookstore and at the Historical Society. Soon, I started to write for a new publication called Charleston magazine. The city, at least, was finding a solid new identity.

Harlan Greene returned to Charleston in 1976 to work as a clerk, archivist, and historian before leaving in the 1990s and returning again. He has not seen his doppelganger in years.

Downtown and Around

Written by Jennet Robinson Alterman

In the summer of ’75, I was living on Queen Street for the second time in my life, renting a third-floor walk-up just a block away from the house where my parents lived when I was born. Queen Street was not posh at either time. The neighborhood was historic but a bit shabby—certainly not part of a “French Quarter.” I paid $90 a month in rent and had a few dollars left for food and necessities. Yet I loved the street, its residents, and my new independence. Without a car, I walked, biked, or bused around town with little congestion or tourists.

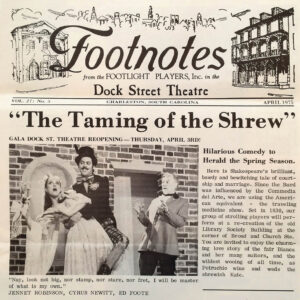

That year stands out because I was doing a lot of acting with the Footlight Players, who performed in the Dock Street Theatre. My father, Emmett Robinson, was the managing director responsible for mounting six productions a year. My mother, Pat, was a playwright and actress. Many people credit them with keeping the arts alive here between the Charleston Renaissance of the early 20th century and the Spoleto Festival.

In 1975, the Dock Street Theatre became one of the first city-owned buildings to be air-conditioned. The Taming of the Shrew reopened the theater after the work was done, and I was thrilled to play the female lead. Air conditioning changed Charleston forever, making tourism a year-round economy.

A few years earlier, I had landed my first job when I learned that WCSC Channel 5 needed a temporary receptionist. I jumped at the opportunity and went on to temp in five departments until being hired full-time in the news department. At Channel 5, I counted Bill Sharpe and Warren Peper among my colleagues. We were all fresh out of college when we started, and thankfully, Loretta Mouzon took us under her wing and showed us how to cover and report the news. A true professional and the first African American woman to report on air in Charleston, she was a real trailblazer, as the city still hadn’t been fully integrated. Her talents were obvious to us rookies. I found out later that in spite of her experience, she was paid less than I was, and I earned less than Bill and Warren. Welcome to the real world.

The country hardly knew about Charleston back then, and Charlestonians didn’t much care what was happening in the rest of the US. Within a couple of years, I was a full-time reporter and anchored the 11 p.m. broadcast, covering a wide variety of news. A couple of major stories from this time still resonate 50 years later.

On the political scene, I had a chance to watch history in the making when the station assigned me to cover Dr. James B. Edwards, a Republican, in his 1974 bid to become governor. It may be hard to comprehend, but South Carolina was solidly Democratic at the time. People assumed that the next governor would be Democrat Charles “Pug” Ravenel, but as often occurs in politics, the unexpected happened. Ravenel ended up ineligible because he did not meet the residency requirement. That left the other Democratic candidate, William Jennings Bryan Dorn, to run against Edwards, a Charleston dentist, who won the Republican primary over retired General William Westmoreland. The gubernatorial race that followed changed South Carolina history and introduced me to one of the finest gentlemen I’ve ever met.

I observed Dr. Edwards exhibit grace and leadership every day during the campaign. On election night, he came to Channel 5 and insisted that I be the first to interview him as Governor-elect, the first Republican governor since 1876. I will never forget his generosity to me during his rise to national prominence.

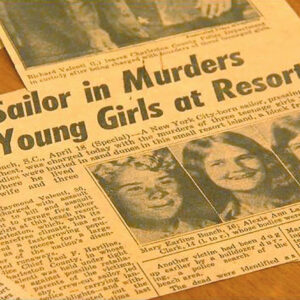

And then there was the grim ongoing story of the “Folly Beach Strangler.” Three girls had been abducted from the beach and murdered. The discovery of their bodies shook the quiet island community to its core. Previously, no one had worried about abductions on our local beaches. It was unthinkable. Folly resident Richard Valenti was charged and given two life sentences. He was denied parole 21 times before he died in 2020.

Although working at Channel 5 broadened my perspectives of world issues and taught me invaluable life lessons, I knew I wouldn’t be in my little apartment on Queen Street for long. I yearned to explore the globe and gain experience beyond my sleepy hometown. I moved away at the end of that summer to chase different dreams, leaving behind a rundown, slightly seedy town with too many vacant lots and a reluctance to fully accept integration. As I ventured forth in an international development career that took me to more than 40 countries, my hometown was growing and learning as well. Under the vision and leadership of Mayor Joe Riley, who took office in December 1975, the city was ripening, beginning to become the jewel that it is today.

Charleston is the place where I was born, and it is the place where I have chosen to settle after four decades of travel. And now I find myself living back on Queen Street in a cherished neighborhood, enveloped in remembrance of times from my past and in a place where I look forward to the future.

Jennet Robinson Alterman is the founding board chair of the Women’s Rights and Empowerment Network that advocates for women and girls in the SC Legislature.

Kiawah Island

Written by Edward O. Marshall

On most weekends in the early 1970s, my family followed a set ritual when journeying from downtown Charleston to Kiawah: Cram blue jeans, boots, and swimsuits into duffle bags and wedge those into the back of my dad’s Oldsmobile station wagon along with our Honda minibike; visit the Piggly Wiggly to stock up on provisions; then hop into the car ready for an adventure. Back then, Kiawah was not yet developed, and wild horses and pigs still roamed free. Needless to say, my siblings and I couldn’t wait to get there.

Dad would drive us out to the end of Bohicket Road where the pavement changed to dirt and the road divided, with Seabrook to the right, a big tomato field straight ahead, and our destination to the left. Cruising down the sandy road, big dust clouds roiled up behind us as we approached the unmanned gate—a single metal pipe barring the way. Our expedition halted, we’d jump out of the car and take our seats on the pipe. When Dad turned his brass key to open the padlock, the rusty chains would drop away, and we’d ride the gate as it swung to open the way onto the island. We’d hop back in the car, more dust clouds dogging us until we rolled over the single-lane, black, creosote-coated timber bridge that spanned the Kiawah River. We loved to see the marsh and pluff mud on either side, because that meant we were almost there.

Following the long road to the ocean, we’d eventually reach Kiawah’s tiny village. Built mostly in the 1950s and ’60s, the comfortable bungalows and beach houses lined the dirt road alongside the water. We’d pass the McDowells’, the Bates’, and the Stallworths’ houses, and others whose owners’ names I’m sorry I don’t recall. A little further on was the Royals’, a big, beautiful home with a real concrete driveway. The Royals owned Kiawah and had invited a handful of other folks to build on the island. Happily, our family was included, and our home was third-to-last running north on the front beach, followed by the Smiths’ and the Sosnowskis’.

My mother, Nancy, and my father, Neil, had built the house—a wonderful place with an exterior crafted of dark redwood that sat up high on black pilings—in the early ’60s. They designed it so that you could see miles out to sea from any room. And because they included two huge glass doors that slid wide open to allow the ocean breeze to flow in and then out through windows facing the road, most of the time, it was cool enough that we didn’t need air conditioning.

Parked under the house was a red Willys Jeep, the means for outings all over the island. One of the best involved Dad driving it over the access roads through the sand dunes to visit the old, abandoned Vanderhorst House. Its walls still stood, but most of the windows were gone, so we were able to creep inside to explore the rooms and walk up the stairs to the top floor, from which we could see all the way to Folly Beach. We heard ghost stories about how a troop of Boy Scouts had stayed in the house and one of the kids was shot through that very window.

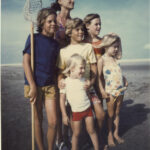

By the 1970s, our family had changed with the times and had come to resemble The Brady Bunch. My father and stepmother, Lynn, brought five kids in all to their marriage, and together we roamed the island like a posse on the minibike and two other motorcycles. We’d visit the northern end of the island and find places where the pigs lived in the marsh grass behind the dunes (we called it “Pig City”) and a huge dune that we dubbed “Pork Chop Hill.”

In 1974, Kiawah was sold to the Kuwaitis, and by the summer of ’75, development was imminent. The island we had known and loved began to fade. While it was hard to witness the changes, Kiawah had provided something eternal—a wonderfully wild and natural place to be a kid, where the memories of our adventures live on.

A former reporter for the News and Courier and Evening Post newspapers, Edward O. Marshall is a psychologist who serves veterans in the Kentucky Department of Veterans Affairs near Lexington, Kentucky, where he lives with his wife, Susan, and son, David.

Mount Pleasant

Written by Ann Thrash

When you’re 13 and can walk, bike, or take a quick boat ride to go everywhere, do everything, and see everybody who’s important to you, life is perfect. That’s what Mount Pleasant was for me in 1975. It wasn’t Mayberry—it was better.

The sprawling city that Mount Pleasant is today, with its 95,000 or so residents, wasn’t imaginable back then, when the town really was a town, with about 10,000 of us calling it home. Life revolved around Coleman Boulevard and “the Village,” where our shopping hub was Pitt Street. There was (and still is) the Pitt Street Pharmacy, which everybody just called “the drugstore.” Coleman’s Hardware was across the street, and next door was Kenny’s, a clothing store. Nearby, at what’s now the Post House restaurant and inn, was a little grocery store that later became a crafts store, where my sisters and I bought supplies for our macramé and decoupage projects. Mom got her permanents at Nan’s Beauty Parlor.

We lived just off Pitt on King Street in the block between the harbor and the present-day Darby Building. One grandmother and my aunt lived next door, and my other grandmother was just a couple of blocks away. We walked to church and Vacation Bible School at St. Andrew’s.

The neighborhood was as tightly woven as a sweetgrass basket. We played foosball in the basement of one neighbor’s house and basketball in the driveway of another. Late on Christmas mornings, all the kids went door to door to see what Santa had brought everybody. My good friend Beth lived down by Alhambra Hall, and we’d ride our bikes to the drugstore on Saturdays for hot dogs at the soda fountain.

In the summer, we spent almost all day, every day, on my grandmother’s dock. We swam like fish, slathered on gallons of baby oil to work on our tans, and caught crabs by the thousands in little drop nets baited with chicken necks. We’d turn down the volume on the pop and rock music from WTMA when the grown-ups joined us. From that dock, we watched the Yorktown being towed into the harbor that summer of ’75, heading to its final berth at Patriots Point with a flotilla of local motorboats and sailboats bobbing alongside it. A generation later, when the Hunley was recovered and returned to port in August 2000, I thought back on the day the “Fighting Lady” arrived and how we waved from the dock and sounded an air horn in salute. As the daughter of a Navy veteran, I felt so proud of the respect my town, and the Lowcountry as a whole, has always had for those who serve at sea.

When the weather and tides were right and dusk was falling, Dad would load up the old rowboat, which he called “the bateau,” and he and I would set out for Crab Bank by kerosene lantern light to go graining, or gigging, for flounder. Mom would bake our catch the next night with a crusting of chopped peanuts—a dish she devised after tasting something similar when she and Dad visited Arnaud’s in New Orleans on their honeymoon.

Dad wasn’t much on eating out (“When I find a restaurant where they cook as well as your mother does, I’ll be happy to go,” he often said.) When we could talk him into it, there was The Trawler or the Lorelei on Shem Creek. The Trawler drew lots of out-of-town visitors, while the Lorelei (located where Shem Creek Park is) had the reputation of being more “local.” I’d get jealous of my sisters, who were a few years older, when their dates would take them to the Blue Hawaii, a Polynesian restaurant on Coleman Boulevard that was the stuff of legend thanks to menu items that we thought were incredibly sophisticated and exotic, such as the pupu platter (an appetizer tray) and a cocktail called the “Flaming Volcano” that would make your head spin (at least that’s what they told us kids).

When the nights turned chilly in the fall, we still gravitated toward the dock. We used larger drop nets rigged with pieces of mullet to catch shrimp—long, fat, red-legged whoppers—by the light of the same kerosene lanterns that lit our way to Crab Bank. That kerosene smell still takes me back to that time. It was all food for a Lowcountry child’s soul.

From my long-ago perspective, Mount Pleasant was self-sufficient. If my parents needed to buy something serious, such as a car or a refrigerator, they had to go to Charleston. But in 1975, everything a child could want or need was “on this side of the bridge,” as we used to say. Even though I now live in Summerton, Mount Pleasant will always be “this side”—the home side of my heart, the place I’ll always return, the place with everything I want and need. Well, except for a Flaming Volcano. Now that I’m legal (and then some), I’d sure like to have one of those.

A former food editor and later features editor of The Post and Courier, Ann Thrash is a freelance writer, editor, and cookbook author. She now lives in Summerton, South Carolina, with her husband, Bill, making quilts and being a dog mom to their Jack Russell terrier, Boomer.

Charleston

Written by Anice Geddis-Carr

In the summer of 1975, I was living in Washington, DC, and homesick for Charleston. It had been several months since I last saw my mother, sister, and brother, and I couldn’t wait for my visit home in August to celebrate my birthday and stay in our house on Fishburne Street, which was filled with warmth, comfort, and much laughter.

I had graduated from Howard University the year before and begun my professional career at Saks Fifth Avenue as a buyer trainee in the exclusive Designer Salon. I loved fashion, and it seemed the perfect fit. But when I received a job offer with the National Bank of Washington that paid well, offered benefits, and allowed me to take care of myself, I couldn’t refuse and became the first African American hired for their commercial loan-training program. This made my mother extremely proud, and I looked forward to sharing the good news with everyone at home.

My mother, Mrs. Wilhelmenia Geddis, was a trailblazer herself, who in 1963 founded Dreamland Nursery & Mickey’s Preschool, the first African-American-owned, licensed day care in the Charleston area. A hardworking, strong woman, she accomplished many of her dreams and shared them through the opportunities she provided for her four children. Recognizing that I was both ambitious and curious, she did whatever it took to make sure I had all I needed, and most of what I wanted.

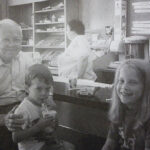

I arrived in Charleston in August for my two-week vacation, looking forward to going on excursions around town and seeing the familiar faces and places I’d been missing. Of course, Mother and I would go shopping, one of our favorite pastimes, at wonderful shops, such as Bob Ellis and Anne’s. And we’d have to go to the Meeting Street Piggly Wiggly with the Harold’s Cabin delicatessen inside. One of Mother’s closest friends, Mrs. Martha Price, worked as a server there, and they had the best deli meats and cheeses. I have been to some fine grocery stores, but Harold’s Cabin couldn’t be matched.

However happy I was to shop on King Street and go to my favorite deli, I became keenly aware that there were no African Americans in management positions in these places. It was hard to reconcile that I would not have had the opportunities afforded me in DC if I had remained in my beloved hometown.

I also remember a Moncks Corner news story from that time about a Black man named Tom Key who had been pulled over and then shot and killed by a white highway patrolman. Many Blacks in the area began to boycott the white-owned stores, but were threatened with the loss of their jobs if their protesting did not end. Today, I can’t help but notice how similar that 1975 murder is to the unjustified killing of Walter Scott by a white police officer a decade ago.

Although my mother was one of the best cooks in town, she believed in exposing us to the finer things in life, so we would often get dressed up in our Sunday best and go out to dine. In the ’70s, it still was not common for African Americans to eat at downtown restaurants, but two of my favorites—the Ladson House on President Street and the Brooks Motel and Restaurant on Morris—were popular among Black people.

I loved the food at Ladson House and how the tables were set with white cloths, china, silver, and nice centerpieces. I remember Mr. Ladson, a tall, stately man who was so gracious to everyone. For its part, the Brooks Motel and Restaurant served great soul food and was known to be a place where you might see someone famous—a Black entertainer, celebrity, or politician (this was where Dr. Martin Luther King stayed during his visit to Charleston). The people there treated us like family, but then again, it was partially owned by my mother’s cousins, Albert Brooks and his brother, Bennie.

It was there that Mother surprised me with a birthday party that summer. She pretended that we were merely going for dinner, but when we walked into the banquet room, there were old classmates from Immaculate Conception School and Bishop England, as well as friends from Burke and Bonds-Wilson and my extended family. What fun we had that night! I had kept in touch with my former schoolmates, and when I came home, we would get together to go dancing at places like Club Zanzibar in the North Area and the Faculty Lounge downtown.

I hold these memories of the summer of ’75 dear because of my wonderful family and all of the special attention I received. But this homecoming also left me with a sad reminder that I was very fortunate. I realized that most African Americans in Charleston would never have the opportunities that I received in DC. I was (and am) fortunate that my mother prepared me to compete in a world that was very different from the one I came from. For that, I will always be grateful.

After pursuing careers (banking) in Washington, DC, and (entertainment) in Los Angeles, Anice Geddis-Carr returned home to care for her mother. Today, she is working in hospitality as a concierge at the Society at Laurens luxury apartments in downtown Charleston.

-

- Anice’s mother, Mrs. Wilhelmenia Geddis, was the first African American to own a licensed day care in Charleston. She passed away in October 2004.

-

- Anice says her mother was responsible for contributing to the success of many up-and-coming Black professionals in Charleston through financial support and mentoring.

James Island

Written by Julian T. Buxton

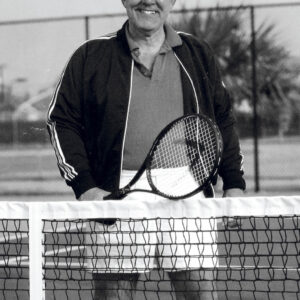

Green, wild, and blue. Other kids built forts or tree houses; I had marsh, saltwater, and sky. Just saying “James Island in 1975” immediately pulls me into the creeks and marshes behind my childhood house. My 15-year-old self could escape school overload, yelling coaches, and six noisy younger siblings by jumping in my johnboat and heading out on James Island Creek. Connected with all of those thoughts is my father, Dr. Julian Thomas Buxton Jr., whose presence was substantial while he lived and remains so to thousands of locals even though he has been gone for more than two decades.

My father lived an outsized life. Not a week goes by without someone recognizing my name and then recounting a story about how my father touched or changed his or her life in some astonishing way. Some of that was through his remarkable energy, physical presence, and demeanor. Much of it was due to his daily surgical work, saving lives on what at some level had to become routine, if that is possible.

My parents bought the North Shore Drive house on James Island Creek in 1964, when Harbor View Road was one of the few paved roads that I can remember. No one imagined a James Island Connector until sometime in the late 1970s, and its advocates seemed nuts to most of us. No one wanted a big bridge to cut through our beautiful marshes, quiet tides, and mostly placid community, including my father. Attitudes changed once it opened in 1993, perhaps my father’s most of all.

Until the connector opened, Dad often spent the night at Roper Hospital if he had patients he needed to watch closely, or if there was a trauma situation. At all other times of emergency, he would race over three bridges—the James Island Creek Bridge (now the Dr. Julian Thomas Buxton Jr. Bridge), the Wappoo Creek Bridge, and the Ashley River Bridge—just to get to the hospital. Far more frequently than now, one of those bridges would be drawn, often putting lives in jeopardy. Occasionally, when the bridges did not block his urgent drive into the city, policemen stopped him for speeding. Upon discovering who he was, they would escort him to Roper with sirens blaring and lights flashing.

Around 2 a.m. one summer night in 1975, I awoke to the sound of the phone ringing. I expected the same thing as usual: no noise for minutes, then a fast, heavy rumbling of the big man coming down the stairs; the front door slamming; and his car engine roaring down North Shore Drive toward the hospital.

On this night, no door slammed after the rumble from the stairs. Instead, the back hall shook as he approached my bedroom. Dad opened the door and told me to get up. He said the Wappoo Creek Bridge was stuck open and commanded me to give him a ride. That made no sense to me, but I sprang out of bed and saw him in the backyard walking with force toward the water. I ran to the dock where he threw me the keys to the Boston Whaler. We jumped in and I throttled the engine full bore across the harbor to the Charleston Marina. I steered the bow toward the floating dock nearest Lockwood Drive. When we got close enough, Dad leaped onto the dock and hit the ground running. I watched him dash toward Calhoun Street until I could no longer see him.

Everything was still and quiet at the dock as I fixed my eyes into the dark, then I headed back home across the water. I like imagining that I was an essential part of a last-minute, heroic saving of a life. The fact is that I never really learned what happened. I didn’t get to ask my father until days later. For three consecutive nights, I heard him speed off to the hospital. One night, he came home from work before I went to sleep, and when I asked, he stood still for a long time. I couldn’t tell whether he was trying to recall which night that was or if he was searching for the right thing to say. The most he offered was, “Yes, thank you very much for what you did. It all worked out.”

That night, my father invited me into something miraculous, something that forever shifted my perspective on how much one life can matter, even though it was, other than the boat ride part, an almost everyday piece of his own life. The experience inspired in me a deep desire to make my time on Earth count.

Now, North Shore Drive and its adjoining streets are paved; most have been for more than 40 years. Twenty years ago, traffic had been so thick and fast during rush hour that my mother and her neighbors successfully petitioned the county to install speed bumps. It’s a far cry from the place where we once rode ponies on a quiet dirt drive and traveled miles from home on our bikes without a care.

And although that boat ride across the harbor is an exalted example, James Island and really all of Charleston contained a wildness and freedom that can’t be fully understood from today’s perspective. 1975 was the year that a doctor colleague of Dad’s, fishing by the jetties at the mouth of the harbor, watched my brother Eddie return from fishing in the ocean. Eddie was nine years old, by himself, in an aluminum johnboat powered only by a six-horse Evinrude. I am not saying that any parent back then condoned such a thing. Yet I am confident that most of us who lived in Charleston in 1975 can produce stories that testify to a time of unfettered exploration and imagination, certainly in comparison to now.

Ellis Island, where Lowe’s and The Peninsula apartments now sit, was an untamed, thick forest with giant live oaks that reached out into the creek. Miles across the green marsh from our houses on North Shore Drive, we 14 and 15-year-old boys spent summer days exploring the whole place. We skinny-dipped with girls, kissed them if they let us, and swung far out into the water on long knotted ropes hung from high branches.

I sound like a nostalgic old man, yet I am only 64, and these memories remain close. James Island has changed significantly since 1975—more development, more people, more traffic. But James Island Creek is still the same. My father and I used to call that creek and its marshes heaven. My mother is still there, and I swear, I believe Dad is too.

Julian T. Buxton III, known exclusively as “Tiger” in 1975, shares the stories of Charleston and the Lowcountry through his 29-year-old company, Tour Charleston LLC. The fifth printing of his cult classic, The Ghosts of Charleston, is on the shelves of Buxton Books, an independent bookstore on King Street that he owns with his wife, Polly.