Parades ♦ Pipers ♦ Provisions ♦ Pubs

In honor of St. Patrick’s Day, the feast day for the patron saint of Ireland, join us on a downtown stroll recognizing the centuries of influence the Irish have had on the Holy City

Written by James Hutchisson carcely a ship sailed from any of Ireland’s ports for Charleston that was not crowded with men, women, and children.” So wrote David Ramsay, the famous local historian, in his journal in the late 18th century upon observing the growing influx of Irish people into the city.

carcely a ship sailed from any of Ireland’s ports for Charleston that was not crowded with men, women, and children.” So wrote David Ramsay, the famous local historian, in his journal in the late 18th century upon observing the growing influx of Irish people into the city.

Escaping heartbreak and tragedy, fleeing famine, wars, and destitution, they left behind their poetic landscape of rolling green fields and dark brown bogs to test their mettle in a new world.

In Charleston, the history of the Irish presence is a history as old as the city itself—a 355-year panoply of achievements by a legendary succession of soldiers, politicians, community leaders, architects, builders, and clerics, all of whom contributed to making the city what it is today. Let’s head to the peninsula and tour some of these historic places and the personalities associated with them.

1

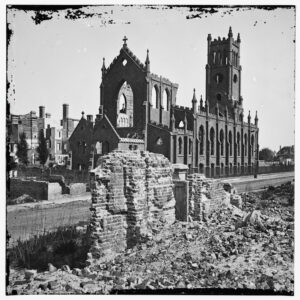

Cathedral of St John the Baptist (120 Broad St.)

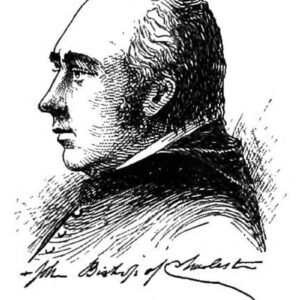

Our starting point is the mother church of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Charleston. Its first bishop was a transplanted Irishman: John England, who was born in Cork in 1786. Tasked by Pope Pius VII with establishing a formal Catholic presence in Georgia and the Carolinas, England arrived in Charleston on December 30, 1820. A tireless advocate of education, he reached out to civic leaders to promote literacy among what was, in large part, a population of poor immigrants.

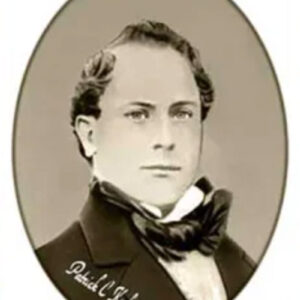

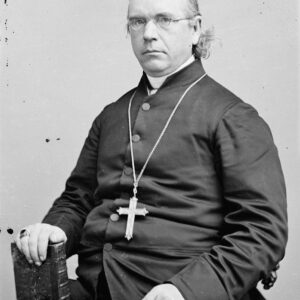

Alas, in the great Charleston fire of 1861, the cathedral (then named St. John and St. Finbar) burned to the ground. It was rebuilt under the leadership of England’s protégé, Bishop Patrick Lynch, appointed the third bishop of Charleston in 1857. Lynch’s family had emigrated to Cheraw, South Carolina, from County Monaghan in 1819. Like his mentor, Lynch took an active role in public welfare and education. He led relief efforts for victims of the Great Famine who fled here in the 1840s, as well as for victims of the yellow fever epidemic in Charleston between August and October 1838: 125 victims of the outbreak were Catholic, 83 of them Irish.

During the Civil War, Lynch was active in humanitarian outreach for all citizens, regardless of political sympathies. After the shelling of Fort Sumter, he cared for wounded Union soldiers and organized a prisoner exchange between the two sides. During Reconstruction, Lynch led efforts to educate freed slaves: in 1866, he purchased a synagogue at 34 Wentworth Street and created St. Peter’s, the city’s first black Catholic parish. It is now the College of Charleston Catholic Student Association.

It took more than four decades to raise the funds needed to rebuild the cathedral, and sadly, Lynch did not live to see the placing of the cornerstone in 1890. For the task, the diocese employed the services of Patrick Keely, known in 19th-century America as the “Prince of Church Architecture.” Born in County Tipperary in 1816, Keely emigrated to New York in 1842 and was said to have designed approximately 600 churches during his career—the large number a sign of the huge influx of Catholic immigrants at the time. The new brownstone cathedral, built in the English Gothic Revival style, opened in 1907, its 219-foot structure eclipsing all other buildings in the city at the time.

Find a schedule of of masses at charlestoncathedral.com

2

The Governor's House (117 Broad St.)

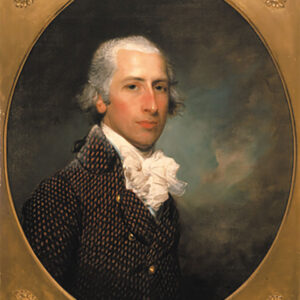

Head across Broad and east about a half block to the Governor’s House, which operated for a time as an inn and is now a private residence. In 1788, it was purchased by Edward Rutledge, son of an Irish physician who had come to Charleston in the 1730s. He was one of four South Carolinians who signed the Declaration of Independence, two from Irish families (the other was Thomas Lynch Jr.). Rutledge later served as the 39th governor of South Carolina.

*This is now a private residence currently undergoing renovations.

3

Honorary Consulate of Ireland for South Carolina (96 Broad. St.)

Continue east past King Street and back to the north side of Broad to the law firm of Duffy & Young, which is also the office of the Honorary Consul of Ireland for South Carolina, Brian Duffy. (You’ll spy the Irish tricolor flag flying.) This honor was given in 2020 to Duffy, the son of retired federal Judge P. Michael Duffy, the charter president of the South Carolina Irish Historical Society, which was founded in 1979 and today boasts upward of 200 members.

4

Charleston County Courthouse (84 Broad St.)

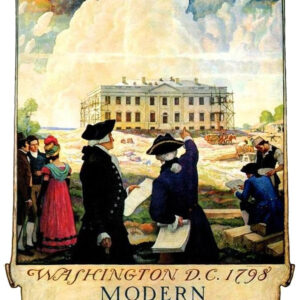

At the intersection of Meeting and Broad lies the Four Corners of Law. On the northwest corner stands the historic courthouse, designed by James Hoban, an immigrant from Kilkenny, who established a successful architectural practice on Trott Street (now part of Wentworth Street) in 1787. A devout Catholic, Hoban was among the original Irish members of St. Mary’s of the Annunciation on Hasell Street—at the time, the mother church of Catholicism when it was in its infancy here. Hoban’s most famous apprentice was Robert Mills, who went on to design the Washington Monument. Hoban himself had the singular honor of designing the White House after meeting George Washington on his visit to Charleston in 1791. They discussed Hoban’s plan for a new executive mansion several times, and when Hoban traveled to the capital to present his design, Washington accepted his proposal immediately—over many others.

Go on a self-guided tour during business hours, Monday-Friday, 8:30 a.m. – 5 p.m.

5

Federal Courthouse and Post Office (83 Broad St.)

Across the street on the southwest corner is the circa-1896 federal complex, the work of John Henry Devereux, by many accounts the most prolific architect in post-Civil War Charleston. Devereux, born in Wexford, Ireland, in 1840, came to Charleston with his parents at the age of three. He began his career as a plasterer and went on to design numerous public buildings and churches in the city, among them the Gothic Revival St. Matthew’s Lutheran Church (1872) at 405 King Street, Stella Maris Catholic Church on Sullivan’s Island (1873), and the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church at 110 Calhoun Street, known as “Mother Emanuel” (1892), the oldest AME church in the South.

Stop by the small postal museum in the lobby, Monday-Friday, 11:30 a.m.-3:30 p.m

6

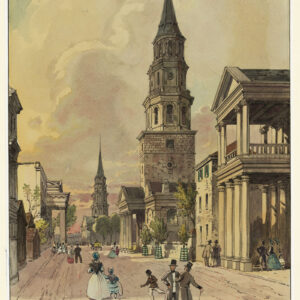

St. Michael's Anglican Church (80 Meeting St.)

Walk across Meeting Street to St. Michael’s Anglican Church, constructed between 1752 and 1761 in the Georgian style. It was built by Samuel Cardy, an immigrant from Dublin. One of the great colonial churches of its time, the massive two-story Tuscan portico that fronts the building is unique in the city, Cardy’s contributions to the design. In their architectural history of Charleston, Albert Simons and Samuel Lapham identified Cardy only as one of “others who applied themselves to architecture,” and wrote that the building was erected according to “plans furnished by a Mr. Gibson.” The latter, some have speculated, may have been James Gibbs, the architect of St. Martin in the Fields Church in London’s Trafalgar Square, with whom Cardy had worked before emigrating to Charleston.

Tour the church and its yard, Monday-Thursday, 9 a.m.-4 p.m., and Friday, 9 a.m.-noon. stmichaelschurch.net

7

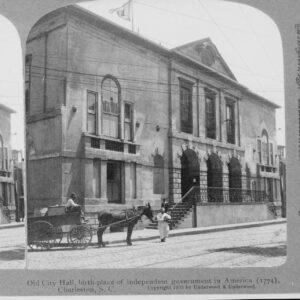

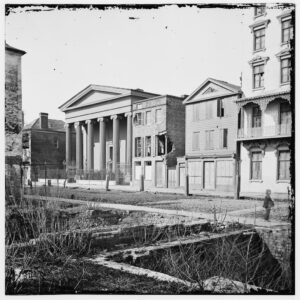

Charleston City Hall (80 Broad St.)

Completing the fourth corner is City Hall, which was originally the First Bank of the United States, circa 1800. Although the design of the neoclassical building is attributed to Gabriel Manigault, its construction, according to architectural historian Kenneth Severens, was largely overseen by Dubliner Edward Magrath, who was an architect in Charleston between 1800 and 1804. It became City Hall and home to the mayor’s office in 1819.

Charleston has had two prominent mayors of Irish descent. The first was John P. Grace, born in Charleston in 1874. A political progressive with strong support among the city’s working class, Grace created what is now the Ports Authority; his company also built the first Cooper River Bridge (known as the Grace Bridge) in 1929, linking the peninsula to Mount Pleasant.

In April 1920, during the Irish War of Independence, Grace brought the Irish statesman Éamon de Valera to Charleston. The future president of the Republic of Ireland and a leader in the Easter Rising of 1916 (the insurrection that tried to bring about an independent Irish state), de Valera gave a rousing speech at the Knights of Columbus Hall at 143 Calhoun Street about the cause of Irish freedom, noting that “the people of this state would readily understand and sympathize, for it was through this port in years past that thousands of Irishmen came to escape…oppression.” (De Valera was originally scheduled to speak at the County Hall on Upper King Street, a public building, but under pressure from anti- Irish factions in the city, Grace was forced to choose a different venue.) A photograph from that time shows Grace and Andrew Riley—grandfather of Joseph P. Riley Jr., who would later become the second notable Irish-American mayor of Charleston—welcoming de Valera to the city.

Like de Valera, Grace was an embattled leader. He served for two nonconsecutive terms, first from 1911-1915 and then from 1919-1923. Both were bitterly contested elections with violent crowds gathering outside polling places that had to be controlled by city police. Grace won the first election by a very narrow margin and lost the second by a mere 28 votes to Thomas P. Stoney, born into a prominent South Carolina family of planters and merchants. Local lore has it that when Joseph P. Riley Jr. was inaugurated in 1976, the then-bishop of Charleston handed him a faded envelope from 1923 with a message in it “for the next Irish mayor.” On the sheet inside were three words: “Get the Stoneys.” Riley would serve as mayor for 40 years. (There will be more about his accomplishments later in the tour.)

Go on a self-guided tour during business hours, Monday-Friday, 9 a.m.-5 p.m.

8

Hibernian Hall (105 Meeting St.)

From City Hall, turn right up Meeting Street to Hibernian Hall, home of the Hibernian Society, founded on St. Patrick’s Day in 1799 for the dual purposes of “true enjoyment and useful beneficence.” The building officially opened on January 20, 1841, and Bishop England gave the oration.

The Hibernian Society (whose members have included both Catholics and Protestants) gave generous assistance, financial and otherwise, to many Irish immigrants. Before the Civil War, most were destitute and unable to find work in the city. In his book, Shamrocks and Pluff Mud: A Glimpse of the Irish in the Southern City of Charleston, South Carolina (BookSurge, 2005), historian Donald M. Williams, notes that between 1830 and 1849, 48 percent of the foreign-born inhabitants of the Charleston poor house were Irish.

While the Hibernian Society presents a small St. Patrick’s Day parade and hosts its private banquet each March 17, it’s the local chapter of another Irish society, the Ancient Order of Hibernians—founded in Ireland in the 1500s, with a local chapter forming in the 1830s—that is credited with reviving the local parade in 1997. However, there is evidence of St. Patrick’s Day celebrations in Charleston dating back to the 18th century, and Williams believes that the earliest formal parade took place in 1823 when a local militia, the Irish Volunteers Company, paraded down Broad Street after a speech by Bishop England.

Included on the National Register of Historic Places, Hibernian Hall is one of the most noticible examples of classical architecture in Charleston. The hall is not open to the public.

10

Joe Riley Waterfront Park (Vendue Range)

Walk across Meeting Street to St. Michael’s Anglican Church, constructed between 1752 and 1761 in the Georgian style. It was built by Samuel Cardy, an immigrant from Dublin. One of the great colonial churches of its time, the massive two-story Tuscan portico that fronts the building is unique in the city, Cardy’s contributions to the design. In their architectural history of Charleston, Albert Simons and Samuel Lapham identified Cardy only as one of “others who applied themselves to architecture,” and wrote that the building was erected according to “plans furnished by a Mr. Gibson.” The latter, some have speculated, may have been James Gibbs, the architect of St. Martin in the Fields Church in London’s Trafalgar Square, with whom Cardy had worked before emigrating to Charleston.

11

Irish Memorial at the Charlotte Street Park (1 Charlotte St.)

-

- A carved granite map of Ireland, the Irish Memorial pays tribute to the contributions of Irish families past and present. On the first Saturday in March at 11 a.m., an event called The Gathering of the Clans takes place on the site, with speakers and a dedication in memory of those who emigrated here.

Hop on a one-mile pedicab ride (or walk) to another Riley triumph, the Irish Memorial at Charlotte Street Park. Erected in 2013 at the end of the small park looking out onto the Cooper River, this joint effort led by the South Carolina Irish Historical Society, the James Hoban Society, the Ancient Order of Hibernians, and others created the 54- by 24-foot carved granite map of Ireland, with names of Charleston’s Irish families engraved on the flagstones surrounding it.

According to Michael Duffy, the city originally proposed Marion Square as its site, but leaders of the Irish community pushed for it to be at the foot of Charlotte Street, down from where many Irish families lived in the old Fourth Ward, Ansonborough, which remained predominantly Irish until the 1950s. (Duffy says older Charlestonians today still sometimes refer to this area simply as “the Borough.”) The spot was the debarkation point for many immigrants arriving in the dismal wake of the Great Famine of the 1840s.

As monuments go, it’s a rather humble tribute, fitting for such a spirited and resilient people—a hinge of history more than a gateway, perhaps, but a stirring symbol nonetheless of what British author G. K. Chesterton called “the rain-wrapped isle” that “looked out at last on a landless sea / And the sun’s last smile.”

Interactive Google Map

Celebrate St. Patrick's Day

On Monday, March 17, the nonprofit Charleston St. Patrick’s Day Parade Committee invites everyone to celebrate the holy feast day with a mass and festivities. Don green and say “Dia duit” (hello in Irish; pronounced jee-ah ghwich) to the city’s Irish sons and daughters, while enjoying appearances by step dancers, fiddlers, fire trucks, military units, bands, and local sports team mascots.

Monday, March 17:

8 a.m. Mass

St. Patrick’s Catholic Church, 134 St. Philip St.

10 a.m. Parade

Grand Marshall Donald M. Williams leads the parade from King and Radcliffe streets, down King to Broad, to its conclusion at the Cathedral of St. John the Baptist.

11:30 a.m. Raising of the Irish flag over City Hall

Sponsored by the South Carolina Irish Historical Society

St. Patrick’s Day Festivities Around Town

CATCH THE LEPRECHAUN 5K – MARCH 15, 2025

Don green apparel and run alongside the mischievous local leprechaun in this 3.1-mile race that begins at Park Avenue Boulevard, heads down to the Darrell Creek Trail, and comes right back to a block party filled with live music, free food, and lucky prizes. Blue Sky Endurance at Carolina Park, 3510 Park Avenue Blvd., Mount Pleasant. Saturday, 8:30-11am. $45-$10.

SHAMROCKIN’ IN THE SQUARE – MARCH 15

Hosted by Summerville DREAM in Hutchinson Square, this lively celebration features Irish music and bagpipes, dance performances, and a variety of food trucks and vendors. Hutchinson Square, 102 S. Main St., Summerville. Saturday, 1-4pm. Free. (843)821-7260,

PATRICK’S DAY BLOCK PARTY & PARADE – MARCH 15

Get decked out in your Saint Patty’s Day-themed gear and head to Park Circle for this popular celebration. The parade kicks off at Park Place East and finishes at Virginia and Jenkins avenues. Enjoy a free block party at the start, which will be hosting specialty street vendors, catering from Olde North Charleston restaurants, live music, and a Kid’s Zone for little ones to enjoy. East Montague Ave., North Charleston. Saturday, noon-5pm. Free. northcharleston.org

Charleston Pipe Band

Local Irish Pubs

Wish your pals sláinte! at these local Irish pubs:

Bumpa’s

Classic Irish pub with locally sourced comfort food and an extensive drink menu

5 Cumberland St.

(843) 952-7565

https://bumpas-chs.com/

Mac’s Place

Festive pub and eatery offering American and Irish dishes, plus TVs for sports fans

215 E. Bay St.

(843) 681-7076

https://macsplacecharleston.com/

Prohibition

Irish-owned modern American restaurant and bar with creative cocktails and a Jazz Age theme

547 King St.

(843) 459-7214

https://www.prohibitioncharleston.com/

Tommy Condon’s Irish Pub & Seafood Restaurant

Family-friendly Irish pub with Lowcountry seafood and live music

160 Church St.

(843) 577-3818

http://tommycondons.com

Ireland’s Own & Jagerhaus Pub

Family-owned restaurant featuring German and Irish fare in a casual setting with live music

3025 Ashley Town Center Dr.

(843) 872-9488

https://irelandsownsc.com/

O’Brion’s Pub & Grille

Cozy, Irish-style hangout with live entertainment, pub grub, and sports on TV.

520 Folly Rd, Ste. 120

(843) 795-0309

Seanachai Whiskey & Cocktail Bar

Cozy pub serving craft cocktails, spirits, and Irish eats, with a beer garden and live music

3157 Maybank Hwy.

(843) 737-4221

https://seanachaiwhiskeyandcocktailbar.com/

O’Brion’s Pub & Grille

Relaxed Irish bar with pub eats, happy hours, a covered patio, and sports viewing

361 N. Shelmore Blvd.

(843) 388-9733

https://obrionspub.com/

Dunleavy’s Pub

A time-honored spot, featuring weekly live folk, country, and acoustic music performances

2213 Middle St., Ste A

(843) 883-9646

https://dunleavysonsullivans.com/

Madra Rua Irish Pub

An authentic pub serving traditional Irish fare, such as shepherd’s pie, plus a variety of brews

1034 E. Montague Ave.

(843) 554-2522

https://www.madraruapub.com/

Madra Rua Irish Pub

Serves Irish pub fare and drafts, with TVs, a mahogany bar, and a dart room

2066 N. Main St.

(843) 821-9434

https://www.madraruapub.com/

O’Lacy’s Pub

Casual Irish sports pub with live music

139 Central Ave.

(843) 832-2999

https://www.facebook.com/olacys/

Fish & Chips with Chip Shop Curry Sauce

Recipe by Prohibition executive chef Greg Garrison

(Yields 2-3 servings)

For the Fish & Chips:

- ¾ cups all-purpose flour

- ¼ cup cornstarch

- 1 tsp. baking powder

- Salt & pepper, to taste

- 1 cup cold beer, like Smithwicks (can substitute sparkling water, if desired)

- 4 cod fillets

- Oil for frying

In a large bowl, mix the flour, cornstarch, baking powder, and a pinch of salt and pepper. Gradually whisk in the beer (or sparkling water) until you have a smooth batter. Allow the batter to rest for 30 minutes.

Heat a frying pan over medium high heat and add oil. Test oil readiness by sprinkling flour in oil. If the flour pops and fizzles away quickly, the oil is ready to fry.

Pat the fish fillets dry with paper towels and season with salt and pepper. Dip each fillet into the batter, allowing excess to drip off. Carefully place each fillet in the hot oil and fry until golden brown and cooked through, about three to four minutes. Remove the fillets to drain on paper towels.

For the Chip Shop Curry Sauce:

(Yields 2 quarts)

- ⅛ cup blend oil (25% olive oil/75% canola)

- 1 tsp. msg

- 3 Gala apples, cored and finely diced

- 2 onions, finely diced

- 2 ½ Tbs. finely minced or grated garlic

- 2 oz. ginger puree

- ¾ cup golden raisins

- 2 tsp. cumin

- 2 tsp. cinnamon

- 2 tsp. turmeric

- 2 ¾ Tbs. Jamaican curry powder

- 2 tsp. ground coriander

- 2 Tbs. sugar

- 4 Tbs. all-purpose flour

- 4 cups chicken stock

- 2 ½ tsp. Worcestershire sauce

- 2 ½ Tbs. tomato paste or puree

In a large sauce pot, heat the oil and msg over medium-high heat. Add the apple, onion, garlic, and ginger and allow to sweat until it is “melty”. Add raisins and stir for one minute. Add cumin, cinnamon, turmeric, curry powder, coriander, and sugar. Stir with a wooden spoon for one minute. Add the flour and stir until it is incorporated. Add Worcestershire and tomato paste. Stir continuously for one minute to cook the flour.

Add stock a little bit at a time, stirring and scraping the bottom of the pot to incorporate the “roux” into the stock. Once all the stock has been added, stir occasionally to ensure nothing sticks or is burnt on the bottom. Bring the sauce to a simmer and cook for one hour on medium-low heat. Remove from heat and blend in batches in a blender. Do not fill the blender.

Plate the fried fish, spoon the desired amount of sauce over each fillet, and serve immediately.

Irish Coffee

Belfast native and Prohibition beverage director Jim McCourt shares the traditional recipe that he perfected as a wee lad in his parents’ restaurant.

( Serves 1 )

- 1 cup heavy cream, freshly whipped for topping

- 1 oz. Bushmills Irish whiskey

- 1/2 oz. simple syrup (2:1 Demerara sugar to water)

- 3 oz. freshly brewed dark roast coffee (Sumatran preferred)

Pour one cup of heavy cream (must be at least 36 percent fat) into a metal bowl or stand mixer. Using either a mixer on medium speed or a hand whisk, whip the cream until it has only slightly thickened and soft peaks have formed, about six to seven minutes (you want the cream to pour easily into the glass). Store the whipped cream in the refrigerator until ready to use.

In a pre-heated Irish coffee glass, add whiskey, simple syrup, and coffee and stir. Float cream on top of the cocktail (about 3/4 inch).

Tip: “A heated glass is key to a good Irish coffee,” McCourt explains. “Before pouring the drink, run your cup under hot water to warm it up.” This emphasizes the hot-cold contrast between the heated coffee and the whipped cream, he says.