An Even-Keeled Guide to Boating in Charleston

Oyster beds, ripping currents, and crowded boat launches: how to navigate the hazards of power-boating in the Lowcountry and have fun while doing it

Written By Stratton Lawrence

Sponsored by:

Charleston’s boundaries are defined by its creeks and rivers, each one a winding path to solitude and immersion in nature. They’re accessed by kayak, paddleboard, jon boat, skiff, or, in my case, aging pontoon. I fish and throw the cast net for shrimp in the fall. Come summertime, I pile a family (or three) in for a day of pulling tubes, sandbar parties, and slow cruises with sunset cocktails. Before the air and water warm in the spring, working from “home” offers some liberties, finding me out on my own, fishing line in the water, laptop on the 2001 Crest pontoon’s table, wonderfully away from it all.

As a port city, we exist because of our access to the ocean. But commercial ships are now far outnumbered (although not outsized) by recreational boats in our waterways. There are more of us on the water than ever before, in a saltwater environment that’s relentlessly unforgiving for rookie boaters. Dramatic tidal swings, strong currents, and submerged oyster beds are among the natural hazards, not to mention the man-made chaos of a busy boat landing on a summer Saturday. Your docking and navigational experience from Lake So-And-So may provide useful background in the Lowcountry, but a wait-your-turn situation at a boat ramp with a ripping current and heavy winds requires a special set of skills.

To write this guide to boating, we gleaned advice from locals who spend their days on the water: a Department of Natural Resources officer, a harbor pilot, a tour boat captain, a marina manager, and a boat storage facility owner.

If you’ve just joined a boat club or are shopping for your first boat, we’ve got you. This guide shows you where to go (and avoid) and how to be safe and legal all day. Even if you’ve been boating for years, it’s useful to brush up. Can you tie a bowline? Is your “throwable” lifesaving device on deck and easily accessible? Should you give that meandering sailboat the right-of-way? (Always.) It’s true—there are no bad days on the water—but only if you’re prepared. Anchors aweigh!

GO EXPLORING

Our waterways can be broken down into three distinct areas:

Charleston Harbor and its tributaries, including the Ashley, Cooper, and Wando rivers

The Folly River ecosystem, including Lighthouse Inlet, the north end of Kiawah Island, and the Stono River

The Intracoastal Waterway from behind Sullivan’s Island up to Bulls Bay

The harbor’s appeal includes fishing, sightseeing along the peninsula, and destinations to eat and drink. The farther you travel north or south, the more likely you are to find a quiet place to anchor by yourself.

Suggested Itineraries

Put in at the Wappoo Cut or Shem Creek Boat Landing (arrive early at either on weekends!). Head up the Cooper River to the west side of Drum Island, facing the peninsula. Anchor on the beach here to relax or beachcomb for shark teeth (make sure your anchor is solid—the currents are strong). Then cruise across the harbor, taking in the views of Fort Sumter, the USS Yorktown, and the Pitt Street Bridge, always being mindful of container ships and commercial traffic in the shipping lane. Finish the day with beers and fried shrimp at Saltwater Cowboys on Shem Creek or at the Charleston Crab House back on the Wappoo Cut.

Put in at the Wappoo Cut or Shem Creek Boat Landing (arrive early at either on weekends!). Head up the Cooper River to the west side of Drum Island, facing the peninsula. Anchor on the beach here to relax or beachcomb for shark teeth (make sure your anchor is solid—the currents are strong). Then cruise across the harbor, taking in the views of Fort Sumter, the USS Yorktown, and the Pitt Street Bridge, always being mindful of container ships and commercial traffic in the shipping lane. Finish the day with beers and fried shrimp at Saltwater Cowboys on Shem Creek or at the Charleston Crab House back on the Wappoo Cut.

Put in at the Folly Beach Boat Landing (alternatives include the Sol Legare and Riverland Terrace landings). Aim for an hour before low tide to anchor on the wide beach at the north end of Kiawah Island. Be careful to follow navigational markers in both the Stono River and the Folly River south of Sunset Cay Marina. After enjoying some beach time, stop at Sunset Cay for a cocktail or continue north through the Folly River to Lighthouse Inlet (take caution through the curves and shoals beginning about a mile after going under the Folly Road bridge). Anchor on Morris Island, or just enjoy the iconic lighthouse from the water.

Put in at the Folly Beach Boat Landing (alternatives include the Sol Legare and Riverland Terrace landings). Aim for an hour before low tide to anchor on the wide beach at the north end of Kiawah Island. Be careful to follow navigational markers in both the Stono River and the Folly River south of Sunset Cay Marina. After enjoying some beach time, stop at Sunset Cay for a cocktail or continue north through the Folly River to Lighthouse Inlet (take caution through the curves and shoals beginning about a mile after going under the Folly Road bridge). Anchor on Morris Island, or just enjoy the iconic lighthouse from the water.

Put in at Shem Creek or Gadsdenville Landing in Awendaw, or pay $50 for the convenience of a launch at Isle of Palms Marina. Either way, you’re headed to your choice of inlet beaches. Dewees Inlet is the closest, and the best beach to anchor on here is the beautiful north end of Isle of Palms. Continue past Dewees to the south end of Capers, a state heritage preserve where you’ll share the beach with dozens of other boaters anchored to enjoy this uninhabited island. It’s a half-mile walk to its boneyard beach. Capers’ north end also has beaches and creeks to explore and receives less boat traffic. Bulls Island, a designated federal wilderness, is just across the inlet.

Put in at Shem Creek or Gadsdenville Landing in Awendaw, or pay $50 for the convenience of a launch at Isle of Palms Marina. Either way, you’re headed to your choice of inlet beaches. Dewees Inlet is the closest, and the best beach to anchor on here is the beautiful north end of Isle of Palms. Continue past Dewees to the south end of Capers, a state heritage preserve where you’ll share the beach with dozens of other boaters anchored to enjoy this uninhabited island. It’s a half-mile walk to its boneyard beach. Capers’ north end also has beaches and creeks to explore and receives less boat traffic. Bulls Island, a designated federal wilderness, is just across the inlet.

Interactive Map

Pre-Trip Prep

Gear

Smart planning is the key to a stress-free day on the water. There are things you’re required to pack, like life jackets and a fire extinguisher, and others that are handy to have, like a first aid kit. Designate a compartment on your boat or a dedicated watertight container for in-a-pinch items like a tool kit and flashlight.

When Officer Rhett Bissell with the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources (DNR) performs a safety check, her first question is often about life jackets. The most common issue is a lack of appropriately sized jackets for children. “If you put a child in an adult life jacket, it completely loses its purpose because they can slip right out of it,” she says.

All jackets must be Coast Guard approved (not a guarantee with many jackets sold online, notes Bissell), and jackets that require inflation may not count unless they’re worn. Note that paddleboarders and kayakers are required to have a life jacket, and, like boaters, a whistle or horn. She also clarifies that the “throwable” floatation device on each boat needs to be readily available—“not buried under the hatch with coolers and beach bags.”

Another common issue is ineffective fire extinguishers. Most have an indicator dial showing their charge or an expiration date. Finally, check that your navigational lights are functional while your boat is still in the driveway or storage facility.

Safety Equipment Checklist

Life jackets in correct sizes for each passenger

“Throwable” floatation device that’s accessible on deck

Fire extinguisher that has not expired

Whistle or air horn

Paddle

Flare gun or other approved distress signal

Working navigation lights

First aid kit

Extra dock lines

Bucket for manual bailing

Tool kit for basic repairs

Charged cell phone

Flashlight

Shoes or boots with strong soles, in case you have to get out of the boat

Sunscreen

Extra gallon or two of drinking water

Emergency stash of nonperishable snacks like energy bars

Weatherly Meadors, owner of Folly Beach-based Tideline Tours, offers courses specifically geared toward women. “Even with the most supportive of husbands, it can be hard to learn boating skills from your partner,” she jokes. The once-a-month, weeknight course covers topics including how to tie knots, basic boat handling, and how to back a trailer.

Planning & Knowledge

tides

Water levels around Charleston fluctuate by about six feet between high and low tides. An oyster bed that’s exposed at low tide may be fully submerged and hidden from sight a few hours later. Every boater should know that day’s high and low tides and be aware of current conditions. Run aground on a rising tide, and you’ll likely be free within an hour. Hit the same spot on a descending tide, and you may have to wait six hours for a full tide cycle before you’re able to float off.

weather

Always check the forecast, especially during summer, when a sunny, cloudless morning can turn into black skies with heavy lightning in a matter of minutes. “If you aren’t expecting a storm to come through and you anchor up on a descending tide, you can be left high and dry in the middle of a thunderstorm,” says Bissell.

boating 101

Take a course that covers everything from how navigational buoys work to understanding right-of-way. Anyone born after July 1, 2007, is required to take an approved boater education course before operating a craft, but older boat drivers are welcome to take DNR’s free six-hour boating class or similar courses offered by the Coast Guard. Sign up at dnr.sc.gov/education/boated.html.

Online courses are also available.

At the Landing

“The most stressful part of boating is dealing with ramps,” says Brooks Geer, co-owner of the Sewee Outpost and a lifelong Lowcountry waterman. “Get to the ramp early,” he recommends. “Don’t wait until noon when it’s crowded, especially if you’re not entirely confident launching your boat.”

Planning ahead for the ramp also means checking the tide. Avoiding mid-tide—especially at ramps like the Wappoo Cut Boat Landing that are known for swift currents—can mean the difference between a happy day on the water and being recorded as the butt of someone else’s joke on social media. “The bigger the boat, the more the wind and current are likely to affect you,” says Jason Teal, a harbor pilot and working mariner for 25 years. “Plan your day to put in and take out at an ebb tide, and a lot of the stress goes out the window.”

Even if you’re comfortable launching in all conditions, there’s still prep to do. Get your boat ready before you block a ramp, so that once it’s your turn, you’re quickly in the water and out of the way. At the end of the day, pull out of the way to prepare your boat for trailering. At the dock, tie off both your bow and your stern while you park or retrieve your vehicle. If you only tie off your bow, your boat may drift off the dock and block two lanes. “Boat ramp etiquette comes down to preparation and being courteous,” says Weatherly Meadors, owner of Folly Beach-based Tideline Tours. “Be helpful and communicate with other boaters.”

Before showing up at a crowded boat landing for the first time, practice backing a trailer into a tight space in an empty parking lot. “Navigating a boat ramp is the biggest barrier to entry for new boaters,” says Geer. “Get comfortable maneuvering your rig somewhere without the pressure.”

On the Water

You’re finally afloat, cruising off on an adventure. But no matter how much you prepare, something could go wrong. “Any veteran boater has learned lessons the hard way,” says Scott Toole, manager of Isle of Palms Marina. “If you haven’t hit an oyster bed, forgotten your bilge plug, or banged up your boat on a dock, then you haven’t really boated.” Avoid catastrophe by following these best practices on the water:

Whenever you’re underway at a speed above idle (“one click above neutral,” says Bissell), the driver is required to wear a kill switch. This simple but critical safety tool connects the ignition to the driver’s life jacket, so that if they fall overboard (a real possibility if you hit a submerged obstacle like an oyster bed at cruising speed), the boat will cut itself off. Otherwise, the vessel continues without the captain, potentially in a circle that could critically injure or kill the driver or other people in the water.

Inlets, channels, and the Intracoastal Waterway often have red and green navigational buoys to help boaters stay in deep water. The rule of thumb is “red, right, return.” (Keep red on your right when you’re headed in). But when you’re headed up or down the coast, knowing whether you’re “returning” can be difficult. In the Intracoastal, keep red on your right when you’re headed south. Note: markers outside of major navigational channels may not be completely up to date. In 2023, some were moved near the Stono Inlet, only for underwater sands to shift during Hurricane Idalia, leaving unnavigable areas within the marked channel at low tide.

Unless you’re an experienced captain in a sportfishing boat, it’s not smart to take your boat into the ocean, even on calm days. The Stono Inlet, Lighthouse Inlet (on the north end of Folly), and Breach Inlet are all notoriously dangerous places to boat. The jetties in Charleston Harbor offer a guaranteed deepwater passage to the ocean, but you’ll share the narrow space with massive container ships that pose their own threats.

Boaters aren’t subject to the “right side of the road,” but as you approach another vessel, indicate your direction as early as possible to allow the other boater to adjust their course.

If you’re in a power boat, cede the right-of-way to sailboats and slower craft like jon boats. And in the harbor and Intracoastal, give ships and commercial boats a wide berth. Meadors says she’s seen small boats puttering alongside tankers, taking pictures. “They can’t stop for you,” she warns.

“Recreational boaters create a lot of stress for us,” agrees Teal, a harbor pilot. “A 1,200-foot-long ship is limited in where it can go.” He recommends switching to channel 13 on radios when you’re in the harbor. He tries to reach boaters in his path on channels 13 and 16 before blowing a ship’s whistle. He also warns boaters against anchoring in shallow areas like the north side of the jetties, where a tanker can create sets of waves at low tide that can swamp a small craft. “If you’re in there in a small boat at low tide, you can be in big trouble,” Teal warns. Even inside the jetties, he recommends using a trolling motor instead of anchoring, since a ship’s wake against the rocks can force a smaller vessel to cut anchor to avoid being washed over.

Charleston’s silty water can mean visibility of less than a foot. Before exiting the boat into water for any reason, check the depth—and for any lurking oyster shoals—with a paddle. Anyone who has cut themselves on an oyster can attest to their razor-sharp shells and the potential for bacterial infection.

If you are on an oyster bed, wait for the tide to float you off. You likely won’t be successful trying to push your boat off by hand. If you do have to exit the boat, wear shoes or boots with strong soles that can withstand sharp shells.

In addition to packing the required safety items, boaters must remain sober. Although it’s legal to have a drink while driving a boat, the same .08 blood-alcohol level that applies to vehicle drivers is valid on the water. Even if you abstain, be aware of your passengers. Hanging off the sides of a boat, bow riding, or standing on the rails are all behaviors that the DNR watches out for on patrol. “If I see people acting crazy, I’ll stop them to go through a safety inspection,” says Bissell.

If you are stopped for any reason, be courteous. “We’re just trying to make sure that everybody onboard is safe and that nobody becomes hurt,” she explains. “We’re not going to stop you for no reason, but if we do stop, we’ll take time to educate you. We’re there to do a job, so just be nice.”

Essential Skills

Boating improves with experience. The more time you spend on the water, the better prepared you’ll be to handle mishaps like running aground. “You’re going to learn some things the hard way,” notes Meadors.

In addition to a boating course, seek out an experienced friend to join you on the water. “The key to gaining confidence is to find a friend who can mentor you,” says Geer. “Even for a 50-year waterman, our saltwater estuaries are a challenging place to navigate.”

And don’t be afraid to recruit a “mentor.” If you’re concerned about an expanse of open water, especially at high tide, wait until another boat comes along and follow them. “When you’re unsure about an area, follow a local and make a track on your GPS for the return trip,” recommends Meadors.

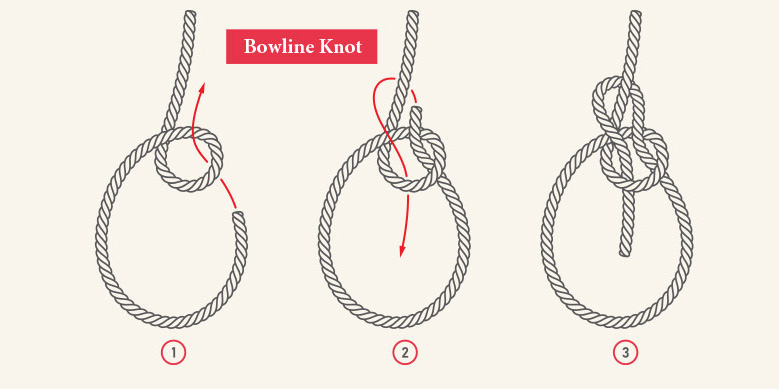

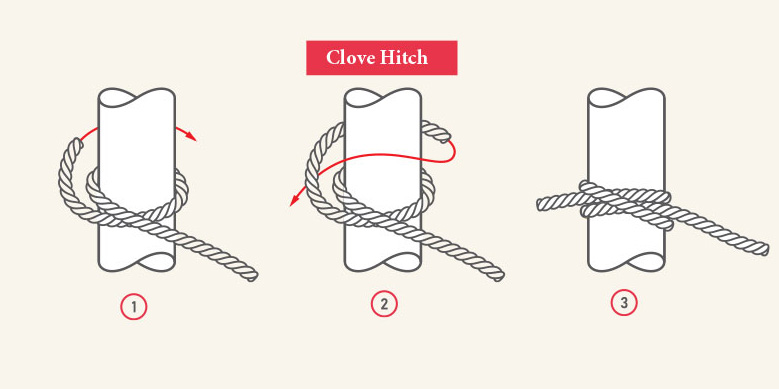

3 Knots Every Boater

Should Know

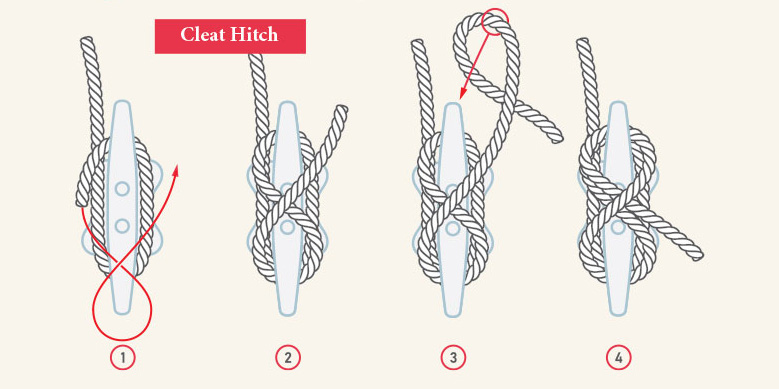

Tying to a Dock Cleat:

Pull the line around whichever cleat horn is further away. Wrap the line around the second horn, before crossing over and under the first horn again. Then, twist the line once to form a loop. Place the loop over the second cleat and pull tight. Coil the excess rope on the dock. “There’s a proper way to tie a boat to a cleat, and plenty of other ways that will probably work,” says Meadors. “Go with the foolproof way.”

Fish Smart

Successfully fishing in Lowcountry waters requires time. You have to gain experience, learning the right techniques and places. If you’re just getting started, here’s some advice to help increase your chance of “going catching.”

Look for birds. If you see birds diving into the water, they’ve found a school of bait, and where there are small fish, there are likely bigger fish swimming nearby.

Know the tide. As the current flows out of a creek mouth on an outgoing tide, redfish and trout ambush small fish. Cast around creek mouths as the tide recedes. Look for seams in the surface of the water—trout prefer moving water.

Use live bait. Artificial lures add to the challenge—and are often as effective as live bait—but pound for pound, month to month, nothing performs like a live shrimp or minnow.

Tow Safely

Few pleasures match the joy of being towed by a boat, whether you prefer skis, a wakeboard, tube, or my family’s chosen inflatable, a giant hot dog. These tips will help keep you safe and maximize your fun.

Scout the area. Don’t tow until you’re 100-percent confident about conditions below and around you. Plan where you’ll make turns, leaving plenty of room between you and oyster beds (remember that you can easily fling a rider into an oyster bank when making a sharp turn).

Look for wind blocks. It’s not as fun to ride in heavy chop—at least not for long. Find a creek with land blocking the wind. Even on a blustery day, you may be able to find a long enough stretch to enjoy smooth rides.

Appoint a spotter. The boat driver’s eyes should stay ahead while towing. Choose a second adult whose job it is to always have eyes on the person or people being towed. Both should know how many people are in the water at all times and where they are. A boat engine should always be in neutral when swimmers are nearby.

Anchor at a Sandbar

A boat opens up the Lowcountry, giving you access to beaches not accessible by car (like on Capers Island) and sandbars that only exist at low tide. These areas become popular gathering places, and anchoring to go ashore can feel as daunting as a crowded boat landing. Although some people prefer to back in with their engine to shore to avoid wakes from other boats coming over the stern, most captains recommend parking with your bow to shore. You may want to nose up to the beach to drop passengers before backing out, dropping your stern anchor, and then slowly moving back to shore until it’s taut. A bow anchor placed in the sand then holds the boat in place. “Try to be as perpendicular to the beach as possible,” says Meadors.

Watch out for your stern line—if it’s too long and running parallel to the beach, it creates a dangerous hazard for another boat that may try to nose in next to you. Even on what appears like a sandy beach, check underwater for oysters before anyone exits the boat. Finally, know the tide. If it’s receding, don’t anchor in too-shallow water or you risk beaching your boat until the incoming tide refloats it.

When you head back out on the water, leave no trace. Pack out all of your trash, and pick up dog poop—it’s a major contributor to fecal coliform bacteria in our waterways.

Choosing a Vessel

There’s no wrong type of boat, but some make the most sense for certain activities. Center consoles are especially popular here. The oval-shaped pathway on their decks allows passengers to move easily to both sides of the boat while fishing. If your main purpose is sunset cruises and entertaining, you may be better off with a deck boat. Flat-bottom boats, like Carolina Skiffs, let you access shallow water (useful for fishing the shallow “flats” where redfish hunt for fiddler crabs), while a “V-hull” offers a smoother ride through choppy water.

Size and seating are often the biggest decision points. “Bigger is not always better,” Geer counsels. “Bigger boats can be harder to handle, in the water and on a trailer.”

Boat Builders

Some of the most prominent hulls manufactured in the Carolinas

Clark Sound: high-end center consoles; Walterboro; clarksoundboats.com

Freeman Boatworks: high-end center consoles built for offshore fishing; Moncks Corner; freemanboatworks.com

Grady-White: premium offshore fishing and cruising center consoles, dual consoles, bay boats, and cabin boats since 1959; Greenville, North Carolina; gradywhite.com

Hatteras: high-end sportfishing yachts; New Bern, North Carolina; hatterasyachts.com

Key West: center consoles built for fishing; Summerville; keywestboats.com

Scout: center consoles and fishing-oriented boats; Summerville; scoutboats.com

Sea Fox: center consoles built for fishing and families; Moncks Corner; seafoxboats.com

Sea Pro: center consoles, bay boats, and offshore fishing boats; Winnsboro; seapromfg.com

Sportsman: center consoles capable of offshore travel; Summerville; sportsmanboatsmfg.com

Stingray: family boats for cruising, towing, and fishing; Hartsville; stingrayboats.com

Join a Boat Club

Nearly every marina in town now offers a boat club. Some are part of a national group (Freedom Boat Club) that offers access to boats both at home and when you travel. Others, like those at marinas owned by Coastal Marinas (including Seabreeze, St. John’s Yacht Harbor, and Isle of Palms), are locally based. Some require an initial fee; all have monthly dues.

“If I have a two-hour window free, now I can get on the water,” says Toole. “I don’t have to spend an hour prepping and cleaning the boat.” Most clubs also require a basic boat safety course before you’re able to take boats out. They also provide the guarantee that you’ll have all the necessary items to be legal in a boat that’s meticulously maintained. Toole recounts a time he was stopped by the Coast Guard with his family. “In my own boat, my registration would probably have been in my office at home,” he admits. “Having that reassurance that your safety equipment and requirements are up to date is huge.”

In addition to clubs, if you’re only an occasional boater, boat rentals are available at the Isle of Palms Marina and at Shem Creek.

Local Clubs

Carefree Boat Club: City Marina (downtown) & Daniel Island Marina; carefreeboats.com

Charleston Boat Club: Ripley Light Marina (West Ashley); boatclubcharleston.com

Destination Boat Clubs Carolinas: The Harborage at Ashley Marina (downtown); destinationboatclubscarolinas.com

Freedom Boat Club: City Marina (downtown), Patriot’s Point (Mount Pleasant), and River’s Edge (North Charleston); freedomboatclub.com

Nautical Boat Club: Wando River Marina (Mount Pleasant); nauticalboatclub.com

PowerTime Charleston: Ashley Marina (Downtown); powertimeboating.com/location/charleston

The following are all managed by Coastal Marinas and enjoy reciprocity:

Bohicket Boat Club (John’s Island); bohicket.com

Isle of Palms Boat Club; iopmarina.com

Old Village Boat Club (Mount Pleasant); ovyc.com

Seabreeze Boat Club (downtown); seabreezemarina.com

St. Johns Boat Club (John’s Island); stjohnsyachtharbor.com

West Ashley Boat Club at Ripley Light Marina; ripleylightyachtclub.com

Back on Shore

Proper care and storage of your boat after a day on the water means you’re less likely to have issues the next time you take it out. The most important step after running your boat in salt water is to flush the engine with fresh water. Some engines have dedicated nozzles to hook up a hose, while others are best flushed using “ear muffs” that clamp over intake ports.

Rinse your entire boat with fresh water, including the trailer (the component most likely to quickly rust and show age in the Lowcountry). Ideally, store it under a cover to protect it from the sun—which ages your vinyl seats—as well as leaves and pollen.

If you don’t plan to use your boat for a while, add a cap of fuel stabilizer to your tank (it’s a smart move every time you fill up). And with most outboard engines, follow manufacturer instructions if they call for ethanol-free gas. Ethanol eats away at hoses and rubber parts inside your engine.

Find a system that works for you, balancing the time required with the fun memories made.

Changing Tides

When Meadors was growing up in the ’90s, she recalls often being the only boat on the water. “We crabbed and fished and took it for granted that everyone on the water had a good respect for the environment,” she recalls. Recently, on Morris Island, she filled a five-gallon bucket with trash and shotgun shells left on the beach. She’s been yelled at after warning people about the $1,000 fine for letting their dogs run through a bird-nesting area, and she’s seen people cruise by boaters in need.

An influx of new residents in Charleston and the prevalence of boat clubs easing the barrier to entry mean more people on the water and at popular anchor-and-chill spots. And more people means more pressure on the environment. But, Meadors points out, all of those people are out to recreate. “It’s fun to be on the water, and having fun puts us in a good mood. So, wave to your fellow boater,” she advises. “Ask if they need help when they appear to be in trouble. Be patient at boat landings and efficient when it’s your turn. If you’re a new boater, take steps to improve your skills.”

“There’s no substitute for experience,” notes Teal. “The more time you spend on the water, the more you’ll learn.”

“At the end of the day, it’s great to see people enjoying the natural resources that draw us to this place,” says Toole. “There’s plenty of wide-open space out there to explore.”